A flock of wild green parakeets just flew over my house, circling and screaming. I can hear them as I sit at my desk, in the home that I’ve made for myself here in the Rio Grande Valley of Deep South Texas.

The parakeets arrive in the early afternoon, often as many as a hundred at a time, to feed in the hackberry trees just outside my studio door. At this moment, their voices sound especially frenetic. Possibly, they’ve spotted a Harris’s hawk and have burst into flight to announce the raptor’s unwelcome presence. The penetrating voices of the parakeets, chanting in unison and clearly audible through the walls of my old adobe home, are a daily phenomenon here, just two miles from the Mexican border.

The Valley is home to thousands of wild parrots. I know because I have counted them often. Since first visiting this most southerly outpost of the Lone Star State eight years ago, I have been drawn ever deeper into the lives of the amazons and parakeets of the Texas frontera. My name is Charles Alexander. I am a wildlife painter, writer, and naturalist. Though born in East Texas and raised in West Tennessee, I feel right at home now in this land of green jays, great kiskadees, and parrots—a place where the birds of tropical Mexico meet and mingle with the birds of the United States.

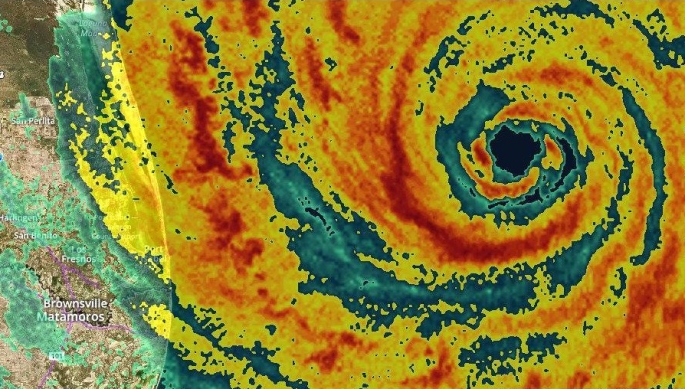

Recently, Hurricane Harvey threatened our world here. On the afternoon of the 24th of August 2017, the door to my studio suddenly flew open as I was rushing to pack away valuables. An unwelcome visitor was calling. The newscasts were unequivocal: Harvey was coming. That afternoon, the storm had undergone rapid intensification in the Bay of Campeche, morphing from a tropical storm into a Category Three hurricane, tracking north by northwest. The wind was picking up.

A relative newcomer to the Valley, I had never experienced a hurricane, much less a tempest of Harvey’s magnitude. My girlfriend Natalie Lindholm—Supervisor of Birds at the Gladys Porter Zoo here in Brownsville—was safely away at a wedding in Washington, D.C. Alone with four cats at the end of our rural road, I began to prepare for the worst: battening down the storm shutters, storing away family mementos, packing away anything fragile or electronic, making that last-minute grocery run —all the while fearing that my studio, archives of photos, paintings, years of wildlife research, all could be wiped out overnight. More urgently, I feared for the lives of our Valley birds, especially the wild parrots. I already knew what could happen in a storm.

The dread of what was approaching took me back five and a half years, to March 29, 2012. On that day, a Thursday, I was nearing the end of my first three weeks of green parakeet field work, a study that I was conducting independently, on my own dime and initiative. Those inaugural days with the Valley’s wild parrots were among the most memorable of my life. I was just getting to know the birds, just beginning to look deeper into the secrets of their turbo-charged existence in McAllen’s urban jungle. The sudden appearance of large flocks of wild parrots in an otherwise ordinary city landscape felt utterly surreal. Every time I turned down 10th Street in search of the birds, I felt as if I had entered a highly-charged corner of my own imagination.

At 10th and Violet in McAllen, literally thousands of parakeets were gathering every evening along the power lines over the street, mesmerizing me with the chaotic din of their collective voices, their comic antics, their flashing, aeronaut wings. Within seeming chaos, however, patterns of behavior were beginning to emerge. Small squadrons of parakeets were constantly arriving to join the nightly roost-rally, with occasional birds diving recklessly down toward heavy traffic, almost touching the tops of vehicles, then zooming at top speed across sidewalks and parking lots to buzz me as they passed. Neatly spaced family units huddled together on the wires overhead, preening each other furiously.

Up and down the lines, the birds were jabbing, squealing, and squabbling with others who dared to infringe upon their clearly-marked and well-understood kinship boundaries. Parakeets were leaping from local rooftops and street signs, balancing airily on the wind, then dashing off to play in the tall palms in another section of the neighborhood. As those initial weeks passed, I realized that I knew so little about wild parrots, that the reality of their lives was far richer than I could have ever imagined. The wild parakeets were teaching me about their true nature. Night after night, I left the birds only when it became too dark to see them anymore.

The March 29 storm hit just after the McAllen parakeets had gone to bed in the palms and live oaks along 10th street, huddled in their close-knit family groups beneath the perpetual twilight of the street lights. The devastation was instant, the storm’s fury unexpected. Between 848 and 941 pm, winds gusting up to seventy-four miles per hour drove quarter to baseball-sized hailstones at hurricane force along 10th Street, defoliating every tree within the impact zone, covering the ground with six inches of pelting ice, and accumulating hail drifts up to four feet high. Torrential rains accompanied the hail, creating ice-water rivers that choked city streets and submerged scores of vehicles in flood zones six feet deep. Lightning flashes electrified the highly-charged night sky from north to south, with strikes setting at least two apartment complexes on fire.

As the storm passed and the hail began to melt, steam rose from the drifts of ice, creating a haze that soon reduced visibility across the city to zero. The storm had knocked out power to more than 25,000 Hidalgo County residents. Over 1,000 homes and businesses were impacted in McAllen. In all, the storm created as much as $300 million dollars in damage, making it one of the costliest to hit the state of Texas since 1950. Before the night was over, more than two hundred people required rescue from hail and wind damaged homes and from the rapidly rising flood waters. Fortunately, few injuries and no fatalities were reported—at least among the city’s human residents.

The next day, I arrived to find my familiar study area along 10th Street reduced to a war zone. Restaurant and office park windows were shattered, a local car dealership totaled. Buildings everywhere looked as if they had been strafed by machine-gun fire. Every leaf on every tree had been plucked, every palm frond shredded, creating a winter-bare landscape in a South Texas spring.

I feared the worst as I walked from 6th Street down to 10th and Violet. Mounds of hail were still melting everywhere I looked, up and down the street. Soon I began to see them: parakeets half-buried in debris, scattered across parking lots and sidewalks, tossed and broken by the storm. Many of the birds had no feathers on one side of their bodies—the hail had plucked them as neatly as it had stripped the leaves from the trees. The smell of death pervaded 10th Street as I searched the neighborhood, picking up parakeets one by one, until I had a garbage-bag full. Each bird looked as if it had been smashed by a hammer. Darkness fell before I could get them all. Driving home exhausted that night, I was reminded of the Robert Frost poem:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

The horror of the McAllen storm became a fresh wound in my memory as Harvey approached the Rio Grande Valley on 8/24/17, five and a half years after impact. If hail could take out so many of the birds that I loved, what would a Cat 3 hurricane do to them, to the many other species of wildlife that call South Texas home?

I had spent years following parakeets by the time Harvey came to call, had come to know individual family groups, had named any oddly marked birds that I was able to identify at a glance. Though many had died, a surprising number of the Valley parakeets had survived the hail in 2012. Could they survive Harvey?

That sleepless night, the great spiraling arms of the hurricane skirted South Padre Island close to home, as Harvey’s eye passed near the Rio Grande Valley, though remaining offshore. I waited for the power to go, braced myself for impact. Neither came, though satellite and wifi were temporarily offline, preventing me from accessing breaking news. I stepped outside to see what was happening, sheltered beneath one of the adobe house’s arched loggias. The atmosphere was sultry, thick with heat and humidity, the night air hard to breathe. At 3am, a strong gust picked up. A squall of near-horizontal rain began, seeming to confirm my worst fears, but the wind almost immediately died away. Near dawn, I drifted off to sleep, waking up suddenly at mid-morning as if expecting the roof to be gone.

Opening my shuttered studio door, I stepped tentatively onto the front gallery, emerging from the house in the still-overcast light of a new day to discover that everything was as it had been before the storm. Nothing had been touched. The huge old ebony trees that shaded the walkway to the road were undamaged, their heavy seed pods still clinging to every bough. Chachalacas were braying from the private wildlife refuge behind our property. Cormorants, egrets, wood storks, and anhingas were perched and preening as usual across our tree-lined road, where a federal refuge protected a wetland fringed with South Texas bushland, a habitat teeming with life and sound. I stood in the middle of the road, marveling that not a single branch was down anywhere, that our Valley world had escaped unscathed. Returning to the house, I paused to watch a column of ants filing across our walkway, putting their world in order. Our mockingbird was singing in an ebony above. Sunlight filtered through the filigreed branches as the clouds began to break.

Our small corner of paradise had been spared. I could continue painting. The parrots would survive, at least for now. In that moment of pure elation, I could never have imagined how many other wondrous wild Edens were about change forever.

To Be Continued…

Part II: Crucible of Storms

Part III: Why Does The Sisserou Matter?

You transport me to another place and time and I ‘feel’ the experience.

LikeLike

Thank you, Pene! I am looking forward to sharing more with you here (and to writing about the Huia for a future project).

LikeLike

Looking spectacular! Thanks for the invitation.

LikeLike

Thank you, David!

LikeLike

Charlie, you are amazing, absolutely brilliant. Love you!!!

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Brenda!

LikeLike

Excellent article. RH

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, RH! Much appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person